It's Ok If You Want To Fuck Count Orlok (But This Is Why)

A reflective essay on Nosferatu 2024, indicating the demise of my paid subscriber ambitions.

I used to love to watch horror movies. I had an archetypal weird girl adolescence that many TikTok addicted Tumblr nostalgists would kill for - watching increasingly fucked up movies cuddled up in my boarding school bed with esoteric Eastern European girlfriends, upping the stakes until one of us finally had to shut the laptop for fear of puking.

As I’ve grown into an adult, I’ve realised the seemingly obvious point that, if you watch horror movies and read horrible books and listen to crime thrillers all the time, you will likely not get better from your anxiety disorder. This is sound advice, so I’ve laid off the horrible stuff since (except Bret Easton Ellis and Irvine Welsh novels, you get a pass).

Nonetheless, I couldn’t resist the pull that Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu, 2024, had on my inner creepy teenager, and I enlisted my most trusted enjoyers of weird shit to accompany me to the Tottenham Court Road Odeon. Dressed all in black, with emo makeup on in an homage to my teenage self (which made for an awkward chance lunch encounter with my partner’s financial sector colleagues), I settled in to watch the first horror film I had seen for some years.

What was it about Nosferatu that lured me back to my old ways? First and foremost, I’m a lover of textiles, and the promise of nepo baby extraordinaire Lily-Rose Depp in expertly designed period costumes was too much to resist. The film promised aestheticism and beautiful garments, and delivered with highly stylised shots of towering snow-topped castles, full skirts in heavy fabrics, dancing gypsies in sequinned wraps, and nude virgins on horseback.

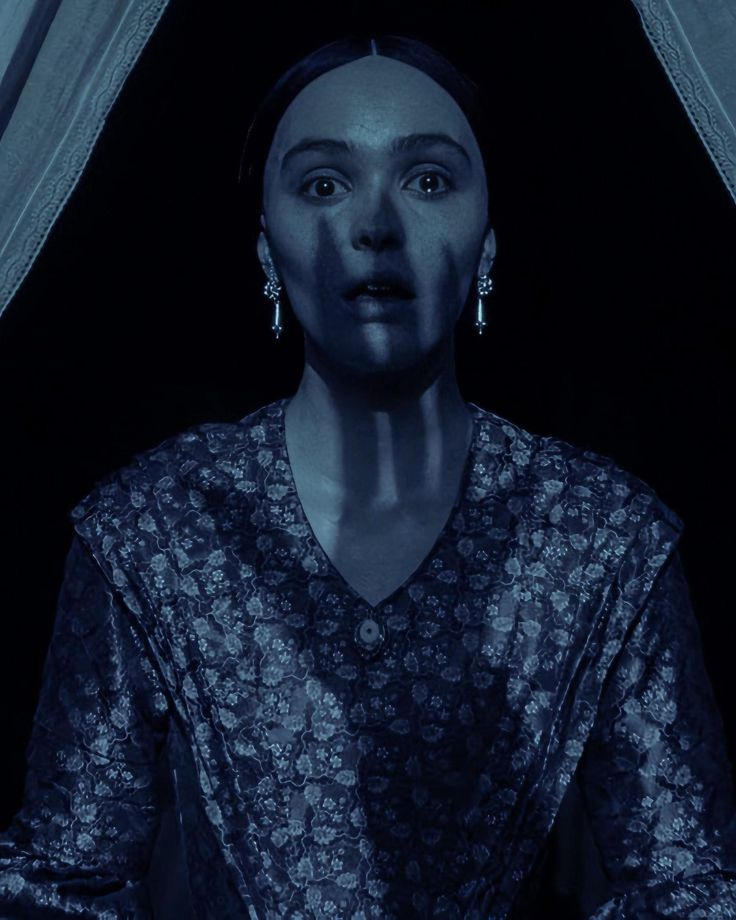

Lily-Rose Depp, despite not being the most expressive of actresses (she essentially makes weak moaning noises or cries mildly for most of the show when not contorting like Linda Blair in The Exorcist), is serene and unnerving as she floats around in ditsy floral gowns. Her high forehead, exacerbated by a long brown wig, gives her the delightful air of an Elizabethan ghost, and she’s every bit the scream queen, drooling and pouring blood from all orifices.

The star-studded cast also includes Nicholas Hoult, who plays main character clueless-estate-agent/golden-retriever-boyfriend Thomas Hutter. There’s no bigger delight to an ex-emo Brit than watching Tony from Skins get systematically drained of blood by Bill Skarsgård in a Transylvanian castle.

Solid performances are given by Emma Corrin as virginal archetypal mother Anna, and Aaron Taylor-Johnson as her down-to-earth, hard-headed husband Friedrich Harding. Skarsgård plays a truly disgusting Count Orlok, Willem Dafoe and Ralph Ineson make an eminently watchable psychiatric doctor pairing, and Simon Mcburney’s Herr Knock… eats a live pigeon whole. I closed my eyes for that bit.

The plot begins with Ellen and Thomas Hutter settling in to marital bliss, with all her psychiatric and spiritual troubles behind her - expect for one small problem. As a lonely, isolated, horny teenager, she summoned and had sex with a vampire, Count Orlok, promising herself to him for all eternity. Years later, he returns to collect on that promise, ruining the lives of those she loves in a quest to make her agree, of her own free will, to bind herself to him once again.

Skarsgård’s iteration of Orlok is particularly disgusting - covered in red sores, surrounded at all times by plague rats, possessed of nasty curly nails, and rotting away to bone where he stands. Nonetheless, this hasn’t stopped netizens, and Nicholas Hoult himself, from vocalising their attraction to Orlok.

The ‘are vampires hot’ debate is not a new one: we all lived through Twilight, and Werner Herzog’s 1979 Nosferatu The Vampyre had fans divided over Klaus Kinski’s sensitive, pining Dracula. Despite Skarsgård’s best efforts to play a truly repulsive character, I left the cinema with a strong notion that I had just seen a film whose main theme was desire.

“What are you even talking about? Women are crazy, I’m convinced.”

I was unsurprised to learn that my counterparts in viewing the film would not, in fact, ‘hear me out’ on this one.

“I’m not saying I fancy him. I’m saying I can see the appeal of obsessive, destructive desire, and it’s difficult to fault a weird, lonely teen for not anticipating the consequences of their actions.”

This Dazed article discusses the trope of the hot vampire in great detail, and argues that Kinski’s 1979 Dracula is an example of true vampiric hotness because of his subversion of what is usually considered ‘sexy’ in popular culture. The argument is that viewers of Nosferatu are attracted to Orlok for obvious, mundane reasons. Skarsgärd’s portrayal of him as a decisive, aggressive, hyper-masculine character is simply the same kind of hot as we find anywhere else: “we can get it anywhere, from mainstream reality TV to Fifty Shades of Grey.”

This idea of the hot vampire as antithesis to men normally considered ‘hot’ is played out most obviously in Twilight, where Taylor Lautner’s ripped, tanned Jacob is contrasted with Robert Pattinson’s pale, thin Edward (here it might be better to visualise the book version in order to get the point).

True as all this may be, today’s cultural environment is uniquely primed to be receptive to the theme of unbridled, ugly, possessive desire in Nosferatu. Just as the eroticism of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula echoes through an era of Victorian sexual repression, Nosferatu shows an ‘unhealthy relationship’ writ large, beaming onto the silver screen the greatest fears of TikTok therapyspeak enthusiasts.

Obsession, possession, unmitigated desire, lunacy, hunger, unsanctioned eroticism: these themes have been replaced in cultural discourse by avoiding toxicity, setting boundaries, unlearning our neuroses, and working out our trauma.

It’s unbelievable I have to make this caveat, but yes, of course I understand it’s not an example of healthy love to imprison someone’s husband, drain them of blood in your Transylvanian castle over the course of several weeks, call a plague onto an entire city, systematically murder and drive insane innocent people around the object of your desire, and then suck all their blood in a weird horrible after-dark sex ritual.

Nonetheless, we have created an online chamber of isolationist discourse in which it’s only ok to want someone to complement your existing life. You must be independent, fully secure, and seeking someone to improve your already perfect situation. You must not hunger for someone, desire them uncontrollably, steal them away from their other commitments, or let them cloud your focus on personal achievements.

Count Orlok is uniquely, vampirically desirable because he does not care about the parameters of ordered life, Ellen’s or his own. The nosferatu is an obvious yet powerful metaphor, pure appetite personified, and fulfils our collective desire for portrayals of transgressive love. Now that themes of forbidden love across cultures, social classes, and genders have been explored to death in Western contemporary cultures, often the only expression of forbidden love we get in popular culture is cheating. Not only has this theme lost the glamorous weight of the old-fashioned affair, but it’s fundamentally just less cool than a supernatural creature from another realm tearing rabidly away at the structures of society in order to fulfil his desire for you.

Skarsgård’s Orlok might be appealing because of his masculinity and possessiveness, but it’s important to remember the aspect of the film that is Ellen struggling with the pleasure her wicked dreams give her. Her possessed self yearns for him in a way that her this-wordly husband can’t satisfy, and ultimately Orlok decides his desire for her blood is worth burning to death in the morning sunlight. Desire, all-consuming and naked, runs through this film as much as the blood and plague bile, and it’s a million miles away from relationships ordered by twice monthly checkins and lists of curated boundaries.

In the (correct) acknowledgement that nobody should feel pressured to pretend to enjoy subversive or power-inflected portrayals of desire, there has been a total overlooking of the fact that some people are genuinely strange, and have fantasies that fall outside the norm. It’s now impossible to articulate that some preferences are truly transgressive and non-mainstream without being accused of being judgemental (“how dare you call anything abnormal”) or a ‘pick-me’ (“that’s not weird, lots of people think that)”. Exploring the type of desire represented in Nosferatu is not something everybody approves of, and nor should it be, but insisting that all art should suit everyone leads to superficial, crowd-pleasing interpretations of complex subjects.

Had Ellen simply focussed on herself and learnt her attachment style, she would not have called out of the window to plead for a release from her loneliness, and none of this would ever have happened. Nonetheless, Orlok’s desirability to a certain demographic doesn’t strike me as surprising, and it represents a refreshing alternative to narratives of desire where the only obstacle is a vague moral commitment to fidelity.

love this 🩷🩷 i also feel it’s very interesting how they intertwined themes of forbidden love with the repression of sexuality - ellen is told to keep her dreams to herself and is forcibly restrained at night in a bid to stop her from expressing herself